A Dive into Geospatial Nearest Neighbor Search

Say you have a list of locations with their corresponding latitudes and longitudes, and you want to put this data to use. Maybe you are a food delivery service that wants to find all Korean restaurants in a 10 kilometer radius. Or maybe you are advertising a job opening in New York but you want to publish it to nearby cities as well. Or maybe you are a dating app that wants to calculate the distance between potential matches to an absurd degree of accuracy.1

While it is very tempting to use the latitude/longitude data as coordinates in a 2-D space and use the L2-norm to compute the “distance” between two locations, the approach fails due to three reasons:

- The earth is not flat: While it is reasonable to consider the Earth to be flat for short distances, its curvature causes noticeable errors in any distance measurements over a few kilometers.

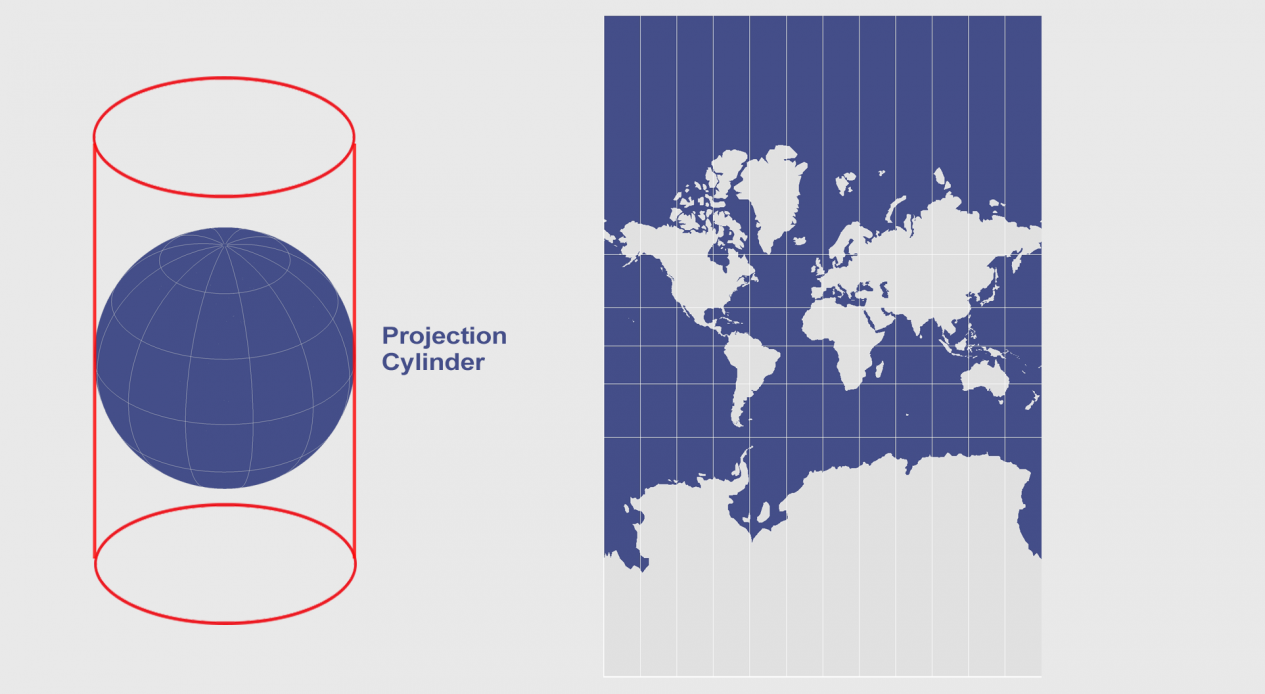

- Equal distances in the geo-coordinate space may or may not be equal in the physical world: The distance required to move 1° along the equator is much larger than the distance required to move 1° near the North Pole due to the curvature of the earth (Figure 1). This makes querying for nearest-neighbors unreliable as some points that may appear to be far away in latitude/longitude coordinate space may actually be closer in real life.

- Latitude/longitude are not continuous at the boundaries of the geo-coordinate space: Latitude/longitude values jump at the prime meridian from +180° to -180° resulting in wrong distance calculations. Similar problems are faced at the North and South Poles where “stepping-over” the poles results in wildly different longitude values.

In this article, we look at a method to compute the distance between two points on the surface of the Earth and extend it to query a geospatial dataset for nearest neighbors.

Figure 1. Mercator Projection is a cylindrical map projection of the Earth. Because the spherical Earth is projected onto a cylinder to get a “flat” coordinate system, the regions near the poles appear much larger than they actually are. Nonetheless, this scheme has been used extensively in the past (for example, Google Maps ditched Mercator projection view for a globe view only in 2018). The scale at which this phenomenon is observed can be interactively experienced at thetruesize.com) [source]

Figure 1. Mercator Projection is a cylindrical map projection of the Earth. Because the spherical Earth is projected onto a cylinder to get a “flat” coordinate system, the regions near the poles appear much larger than they actually are. Nonetheless, this scheme has been used extensively in the past (for example, Google Maps ditched Mercator projection view for a globe view only in 2018). The scale at which this phenomenon is observed can be interactively experienced at thetruesize.com) [source]

A better distance function

Note 1: A key assumption here onwards is that the Earth is spherical in shape, which is not strictly true as the Earth’s shape is closer to an ellipsoid with the radius of curvature at the equator being ≈6378 km and that at the poles being ≈6357 km. Because the difference in the radius is not large, the error is generally small enough to be safely ignored.

The shortest distance between any two points on a sphere is the distance between the two points along the great circle passing through both the points. A great circle is a circle drawn on a sphere with the same radius as the sphere, and centred at the centre of the sphere. Of the infinitely many great circles possible, we are now concerned with the one that passes through the two points in question.

The solution to finding the distance between two points along the Earth’s surface lies in using the latitude/longitude values to compute the central angle between them. The central angle \(\theta\) is defined as:

\[\begin{equation} \theta = \frac{d}{r} \tag{1}\label{eq:1} \end{equation}\]where \(d\) is the distance between the two points along the great circle, and \(r\) is the radius of the sphere. Because we already know the mean radius of the Earth (6371008.7714 m2), in order to find the value of \(d\), we need to compute \(\theta\).

Let’s put this knowledge to use.

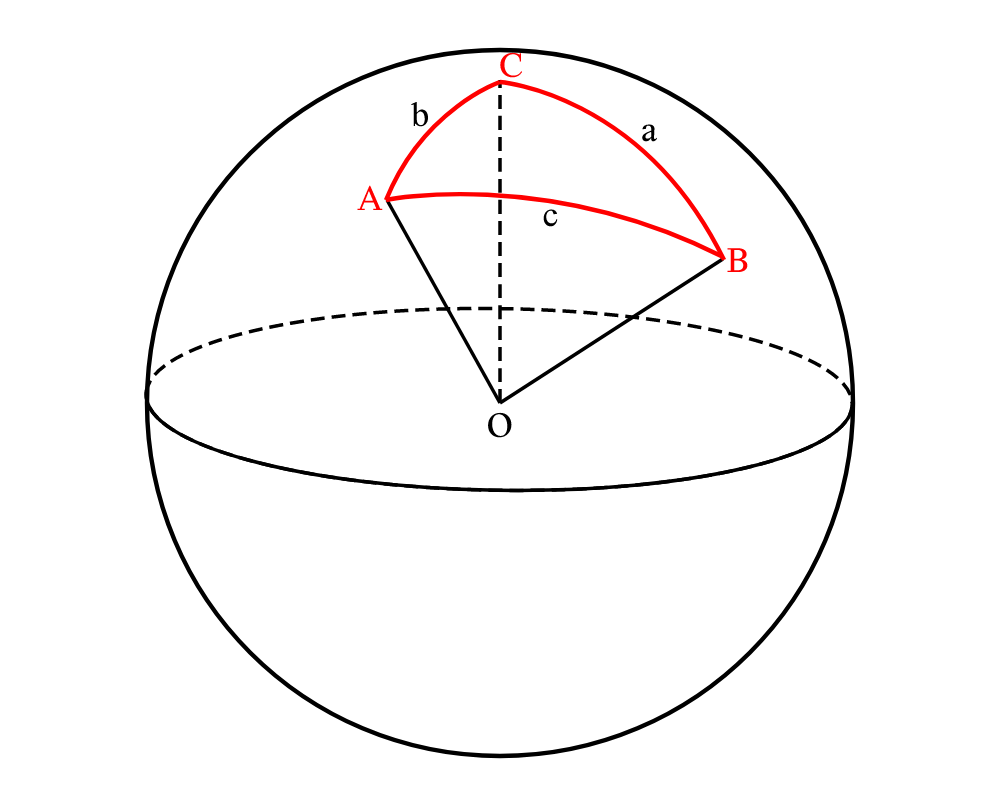

Let points A and B be two points on the surface of the Earth with latitudes \(\phi_1\) and \(\phi_2\) and longitudes \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) respectively, and let C be the North Pole. a, b, and c are the lengths of the arcs created by BC, AC and AB respectively on the surface of the sphere. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. A, B, and C are three points on the Earth’s surface, and O is the center of the Earth.

Figure 2. A, B, and C are three points on the Earth’s surface, and O is the center of the Earth.

If we consider the sphere in Figure 2 to be of unit radius, then using \(eq. \eqref{eq:1}\), the \(\angle AOB\) is the same as \(c\), \(\angle AOC\) is the same as \(b\), and \(\angle BOC\) is the same as \(a\).

Now, we have \(c = \theta\), \(b = \frac{\pi}{2} - \phi_1\), \(a = \frac{\pi}{2} - \phi_2\), and \(C = \lambda_2 - \lambda_1\).

Using the spherical cosine rule:

\[\begin{equation} \cos c = \cos b \cos a + \sin b \sin a \cos C \end{equation}\]we get:

Replacing \(\theta\) with \(d\) and using \(\sin^2(\frac{x}{2}) = \frac{1}{2} (1 - \cos x)\), we get

For a sphere with radius \(R\), the above equation changes to

This formula has been around for a long time, but it is cumbersome to use without a calculator. It requires multiple trignometric lookups, calculating squares, and even a square root. To simplify the calculations, we use a lesser known trignometric function haversine, which is defined as:

Using this definition in \(eq. \eqref{eq:2}\), we get what is called the Haversine formula:

In the past few hundred years, the Haversine formula has been used extensively by sailors in planning their voyages.3 Instead of multiple difficult operations required by \(eq.\eqref{eq:2}\), this formula makes it really simple to perform the calculation by requiring only a few lookups in the haversine table.

Implementation in Python

Let’s compute some distances! We will be using an openly available dataset of US Zip-codes and their corresponding latitude and longitude values. Also, we will be using \(eq.\eqref{eq:2}\) instead of \(eq.\eqref{eq:3}\) because we aren’t nineteenth centure sailors, and also because computing sin, cos, squares, and square roots has become trivial.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

R = 6371008.7714

def haversine_distance(lat_1, lon_1, lat_2, lon_2):

return 2 * R * (np.arcsin((np.sin((lat_2 - lat_1) / 2) ** 2 + \

np.cos(lat_1) * np.cos(lat_2) * \

np.sin((lon_2 - lon_1) / 2) ** 2) ** 0.5))

if __name__ == "__main__":

# list of US zip codes along with their respective latitudes and longitudes

df = pd.read_csv(

"https://public.opendatasoft.com/explore/dataset/us-zip-code-latitude-and-longitude/download/?format=csv&timezone=Asia/Kolkata&lang=en&use_labels_for_header=true&csv_separator=%3B",

sep=";")

df = df.drop(columns=["Timezone", "Daylight savings time flag", "geopoint"])

df = df.set_index("Zip")

print(df)

# convert degrees to radians

df.Latitude = df.Latitude.apply(np.radians)

df.Longitude = df.Longitude.apply(np.radians)

# compute distance between 68460 (Waco, NE) and 80741 (Merino, CO)

lat_1, lon_1 = df.loc[68460][["Latitude", "Longitude"]]

lat_2, lon_2 = df.loc[80741][["Latitude", "Longitude"]]

distance = haversine_distance(lat_1, lon_1, lat_2, lon_2)

print(f"The distance between 68460 (Waco, NE) and 80741 (Merino, CO) is {distance / 1000:.2f} km.")

# compute distance between 50049 (Chariton, IA) and 51063 (Whiting, IA)

lat_1, lon_1 = df.loc[50049][["Latitude", "Longitude"]]

lat_2, lon_2 = df.loc[51063][["Latitude", "Longitude"]]

distance = haversine_distance(lat_1, lon_1, lat_2, lon_2)

print(f"The distance between 50049 (Chariton, IA) and 51063 (Whiting, IA) is {distance / 1000:.2f} km.")The script produces the following output:

City State Latitude Longitude

Zip

38732 Cleveland MS 33.749149 -90.713290

47872 Rockville IN 39.758142 -87.175400

50049 Chariton IA 41.028910 -93.298570

48463 Otisville MI 43.167457 -83.525420

51063 Whiting IA 42.137272 -96.166480

... ... ... ... ...

68460 Waco NE 40.897974 -97.450720

28731 Flat Rock NC 35.270682 -82.415150

74362 Pryor OK 36.292495 -95.222792

37049 Cross Plains TN 36.548569 -86.679070

80741 Merino CO 40.508131 -103.418150

[43191 rows x 4 columns]

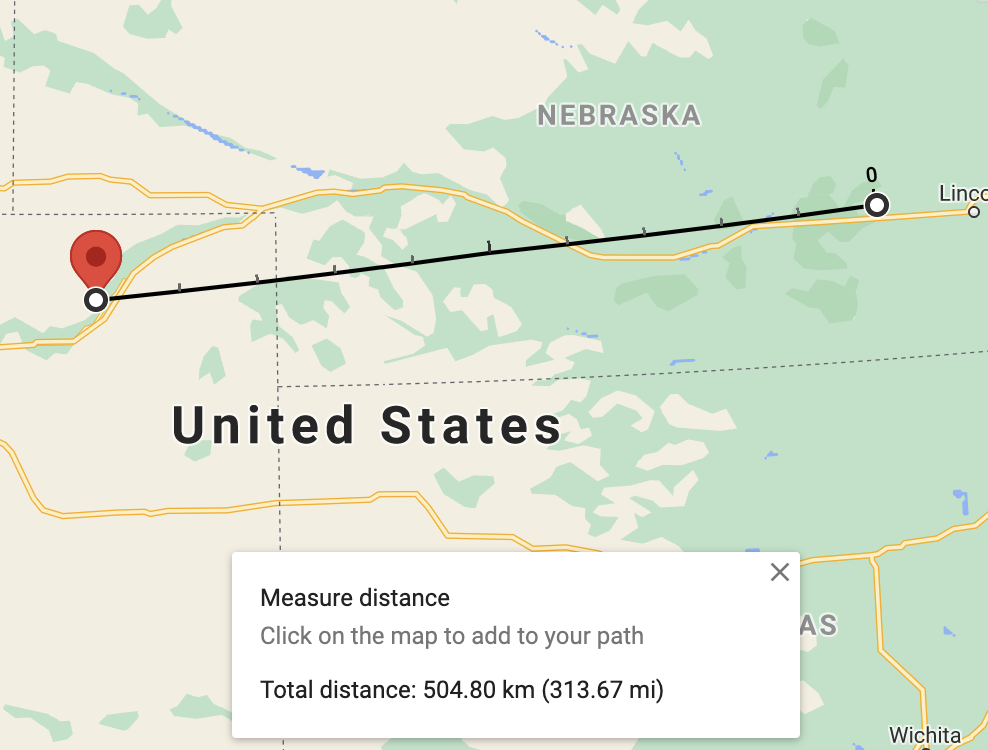

The distance between 68460 (Waco, NE) and 80741 (Merino, CO) is 504.80 km.

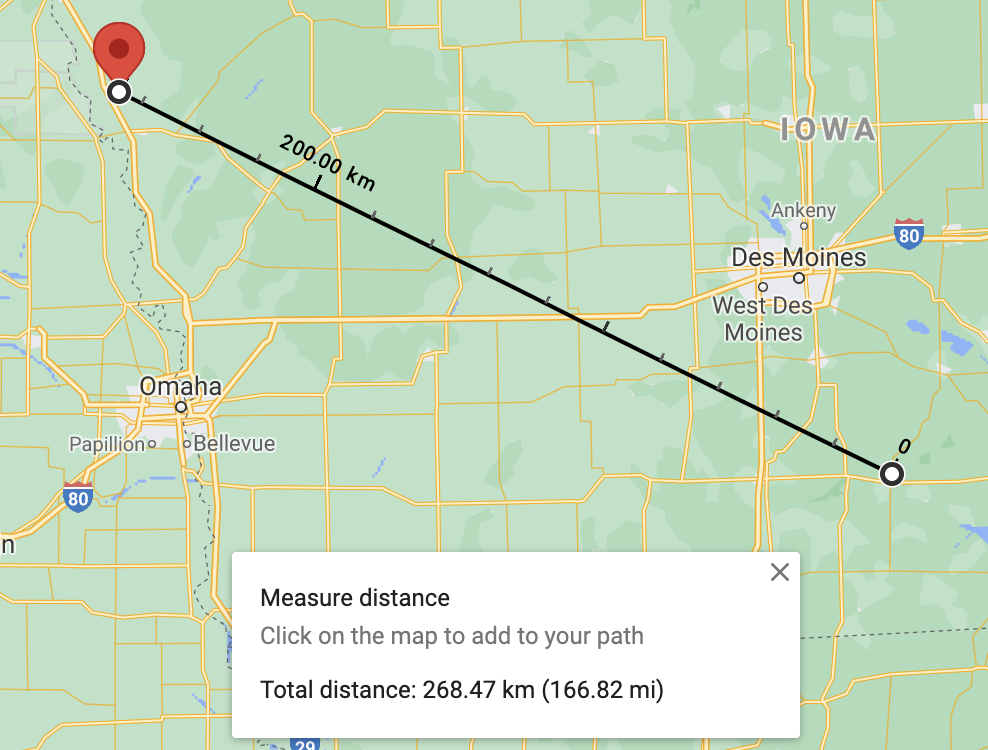

The distance between 50049 (Chariton, IA) and 51063 (Whiting, IA) is 268.47 km.

We can compare our results against the results obtained from Google Maps:

Distance from Waco, NE to Merino, CO using Google Maps Distance from Waco, NE to Merino, CO using Google Maps |

Distance from Chariton, IA to Whiting, IA using Google Maps Distance from Chariton, IA to Whiting, IA using Google Maps |

The query mechanism

Now that we have a reliable distance metric in place, let’s shift our focus to querying our data for nearest-neighbors. We are primarily interested in two kinds of queries:

- finding \(k\) nearest neighbors (kNN) of a given point, and

- finding all neighbors in radius \(r\) around a given point

The brute-force method

The most obvious way to perform queries of these types is the brute force approach. For any given point, we simply iterate over all other points in our dataset and compute each point’s distance from the given query point. Under the standard assumption that the query point may not be present in the dataset, the brute-force approach has \(O(D.N)\) (where D is the dimensionality of the data, which in our case is 2) time complexity. Iterating over all data points for a query is very computationally expensive, especially if the size of the data is large. To speed up the query mechanism, we now look into preprocessing algorithms that can take advantage of its inherent structure.

The (problematic) k-d Tree

A standard approach to optimize the brute-force approach is to use a specialized tree data structure called a k-d tree. A k-d tree, or a k-dimensional tree, is a binary tree which recursively splits the space into two by building hyperplanes. A hyperplane is defined as a subspace whose dimension is one less than the dimension of its ambient space (a hyperplane in 2D is a 1D line, a hyperplane in 3D is a 2D place, etc.). Each node is associated with an axes and represents a hyperplane that splits the subtree’s search space perpendicular to its associated axis. All points on one side of this hyperplane form the left subtree, and all points on the other side form the right subtree. All nodes at the same level in a k-d tree are associated with the same axes.

The splitting planes are cycled through as we move down the levels of the tree. For example, in a 2-dimensional space, we would alternate between splitting perpendicular to the x-axis and to the y-axis at each level (Video 1)4. In a 3-dimensional space, the root would be split perpendicular to the x-y and x-z planes, the children would be split perpendicular to the x-y and y-z planes, the grandchildren perpendicular to the x-z and y-z planes, the great-grandchildren again perpendiculat to the x-y and x-z planes, and so on.

Video 1. k-d tree in 2-dimensions: While constructing a k-d tree, we alternate between splitting perpendicular to the x-axis and perpendicular to the y-axis at each level of the tree. Each split is made at the median of all the points in the subtree along the associated axis of that level.

Once the tree has been constructed, searching and range queries are quite simple to execute. For either type of query, we traverse the tree from the root until we reach the leaf node that would contain the query point. Then:

- For k-nearest neighbor search:

- All points in the leaf node’s search space become the candidate points for k-nearest neighbors and each point’s distance from the query point is calculated.

- If the maximum distance \(m\) amongst the \(min(num(candidate\_points), k)\) nearest candidate points exceeds the distance from the query point to the boundary of any neighboring subspaces (or, if a hypersphere of radius \(m\) centered at the query point intersects with any hyperplane), then the neighboring subspace’s points are also added to the candidate points set.

- This is repeated until we have at least \(k\) candidate points and the distance to the k-th farthest candidate point is lesser than the distance to the nearest neighboring subspace. Finally, the k-nearest candidate points are selected as the result.

- For range queries within a radius \(r\) about a query point:

- All points in this search space are added to the candidate points set, and points from all neighboring subspaces which are at a distance less than \(r\) from the query point are also added to the candidate points set.

- All points that are at a distance less than \(r\) from the query point are selected as the result.

The tree construction has a time complexity of \(O(N\log(N))\), and the kNN and range queries have a time complexity of \(O(\log(N))\) and \(O\left(D. n ^ {1 - \frac{1}{D}}\right)\) respectively, where \(D\) is the dimension of the data, which in our case is 2.

As k-d trees can split the space only along the axes, they only work with Minkowski distances such as Manhattan distance (L1 norm) and Euclidean distance (L2 Norm). Unfortunately for us, the Haversine distance metric is not a Minkowski distance. We now build upon the basic concepts of the k-d tree, and look at a data structure that does not depend on the explicit coordinates of each point, but only on the distance metric.

The Ball Tree

A ball tree is similar to a k-d tree in that it too is a space partitioning tree data structure, but instead of using hyperplanes to partition the data it uses hyperspheres (or “balls”; a hypersphere in 2-dimensions is a circle, and a hypersphere in 3-dimensions is a sphere or a ball). A ball tree works with any metric that respects the triangle inequality:

\[\left|x+y\right| \leq \left|x\right| + \left|y\right|\]At each node of the tree, we select two points in the data that have the maximum pairwise-distance between them. Using the same distance metric, all other points in the subtree are assigned to one these two points. Using the centers, we create two hyperspheres that span the points associated with the respective centers. Each of the newly formed hyperspheres may now be further divided into two hyperspheres each, and this process continues recursively until a stopping condition is reached (a certain depth is reached, or each leaf node has fewer than a specified minimum number of data points, etc).

Video 2. Ball tree in 2-dimensions: The two points with the largest pair-wise distance are selected, and are considered the center of a hypersphere. All points are assigned to the center that is closest to them, and two hypersphere of radius same as the distance of their center to the farthest associated point are created. These hyperspheres are further broken down into two hyperspheres each, and this process continues recursively.

Note 2: Instead of considering the two farthest points to be the centers of the hyperspheres, we can also use the centroid of each cluster. This approach results in tighter spheres and more efficient queries, but it is not possible to use with non-Minkowski distances as computing the centroid in over them is an ill-defined problem.

Nearest neighbor search and range query are very similar to those on a k-d tree: we traverse the tree and reach the lead node that would contain the query point. If the query point lies outside of either hypersphere at any level, we assign it to the hypersphere who’s center is at the least distance from the query point. Then,

- For k-nearest neighbor search:

- All points in the leaf hypersphere are now considered to be the candidate points.

- A minimum bounding hypersphere for the \(min(num(candidate\_points), k)\) nearest candidate points is considered, and the points from all other hyperspheres that intersect with the minimum bounding hypersphere are added to the candidate points set.

- As with a k-d tree, this process is repeated until there are at least \(k\) candidate points, and the distance to the k-th farthest candidate point is lesser than the distance to the boundary of the nearest neighboring hypersphere. The \(k\) nearest candidate points are then selected as the result.

- For range queries within a radius \(r\):

- All points in the leaf node’s search space are added to the candidate points set, and points from all hyperspheres that intersect with the candidate points’ minimum bounding hypersphere are also added to the candidate points set.

- The points that are at a distance less than \(r\) from the query point are selected as the result.

Distance from a point to a hypersphere’s surface is very simple to calculate. We just calculate the distance from the point to the hypersphere’s center and subtract the radius. More formally, for a hypersphere of radius \(r\) centered at point \(center\), the distance from a point \(query\_point\) is defined as:

Hyperspheres thus make for a very efficient query mechanism as computing distance to a hypersphere is significantly simpler than computing distance to any other n-dimensional geometric structure. This property holds true for non-Minkowski distances as well.

The time complexity for tree creation for a general ball tree using a non-Minkowski distance metric is \(O(N^2)\). The kNN and range queries have time complexities same as those of a k-d tree, i.e., \(O(N\log(N))\) and \(O\left(D. n ^ {1 - \frac{1}{D}}\right)\) repectively.

Note 3: Using a Minkowski distance metric and the method described in Note 2, the tree construction time complexity drops to \(O(N\log(N))\)

Implementation in Python

Let’s put everything together in a few lines of Python code. The scikit-learn library has a nice implementation of BallTree with support for Haversine distance right out of the box.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from sklearn.neighbors import BallTree

R = 6371008.7714

if __name__ == "__main__":

df = pd.read_csv(

"https://public.opendatasoft.com/explore/dataset/us-zip-code-latitude-and-longitude/download/?format=csv&timezone=Asia/Kolkata&lang=en&use_labels_for_header=true&csv_separator=%3B",

sep=";")

df = df.drop(columns=["Timezone", "Daylight savings time flag", "geopoint"])

df = df.set_index("Zip")

# convert degrees to radians

df.Latitude = df.Latitude.apply(np.radians)

df.Longitude = df.Longitude.apply(np.radians)

# construct a ball tree with haversine distance as the metric

tree = BallTree(df[['Latitude', 'Longitude']].values, leaf_size=2, metric='haversine')

# lets find the 10 nearest zipcodes to a 68460, a zipcode in Waco, NE

query_zipcode = 68460

query_point = df.loc[query_zipcode][["Latitude", "Longitude"]].values

distances, indices = tree.query([query_point], k=10)

result_df = df.iloc[indices[0]]

result_df['Distance (in km)'] = distances[0] * R/1000

print(f"The 10 closest zipcodes to {query_zipcode} are:")

print(result_df)

print()

# lets find all the zipcodes in a 25 km radius of 68460, a zipcode in Waco NE

indices, distances = tree.query_radius([query_point], r=25/(R/1000), return_distance=True, sort_results=True)

result_df = df.iloc[indices[0]]

result_df['Distance (in km)'] = distances[0] * R/1000

print(f"The zipcodes in a 25 km radius of {query_zipcode} are:")

print(result_df)The script produces the following output:

The 10 closest zipcodes to 68460 are:

City State Latitude Longitude Distance (in km)

Zip

68460 Waco NE 0.713804 -1.700836 0.000000

68456 Utica NE 0.713810 -1.698569 10.916424

68467 York NE 0.713233 -1.703247 12.169037

68367 Gresham NE 0.716272 -1.699893 16.363419

68316 Benedict NE 0.715839 -1.703610 18.605159

68313 Beaver Crossing NE 0.711776 -1.697655 20.047743

68401 McCool Junction NE 0.711132 -1.703144 20.340898

68364 Goehner NE 0.712664 -1.696812 20.701203

68330 Cordova NE 0.710632 -1.699116 21.845466

68439 Staplehurst NE 0.715517 -1.696551 23.330794

The zipcodes in a 25 km radius of 68460 are:

City State Latitude Longitude Distance (in km)

Zip

68460 Waco NE 0.713804 -1.700836 0.000000

68456 Utica NE 0.713810 -1.698569 10.916424

68467 York NE 0.713233 -1.703247 12.169037

68367 Gresham NE 0.716272 -1.699893 16.363419

68316 Benedict NE 0.715839 -1.703610 18.605159

68313 Beaver Crossing NE 0.711776 -1.697655 20.047743

68401 McCool Junction NE 0.711132 -1.703144 20.340898

68364 Goehner NE 0.712664 -1.696812 20.701203

68330 Cordova NE 0.710632 -1.699116 21.845466

68439 Staplehurst NE 0.715517 -1.696551 23.330794

Further reading

If you found the article and its premise interesting, here are some other interesting resources:

- Replacing Haversine distance with a simple machine learning model (InstaCart blog).

- We assumed that the Earth is a perfect sphere. But we know that it isn’t. Vincenty’s method considers the Earth to be an spheroid and provides a more accurate distance metric.

- Benchmarking Nearest Neighbor Searches in Python

Footnotes

-

Inman, James (1835). Navigation and Nautical Astronomy: For the Use of British Seamen (3 ed.). London, UK: W. Woodward, C. & J. Rivington. ↩

-

All videos created using Manim Community. ↩